UK productivity is lower than in France, Germany and United States – and almost all of this gap is due to a lack of investment in capital and skills, new analysis from the London School of Economics and Political Science shows.

The report Cracking the productivity code: An international comparison of UK productivity, published by the LSE’s Programme on Innovation and Diffusion (POID) compares UK productivity to that in France, Germany and the United States. It shows that the productivity slowdown that began after the global financial crisis was an international phenomenon, but the UK suffered a larger slowdown than other nations.

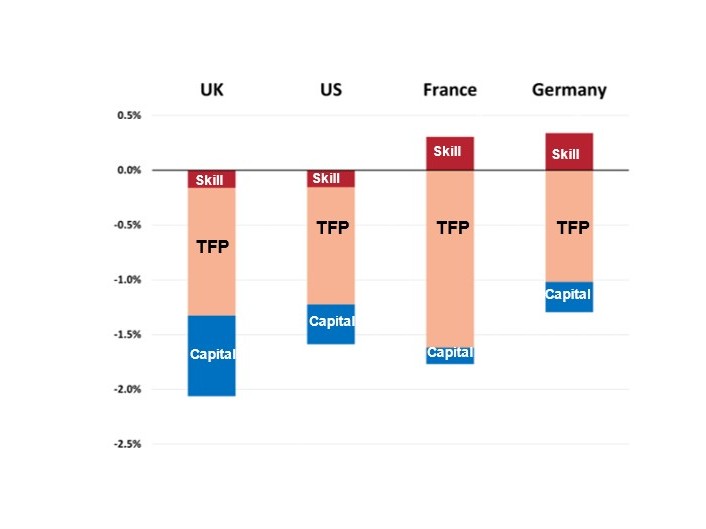

Some of the factors behind the slowdown were global – affecting all these countries to a similar extent. But about half of the slowdown in the UK is due to a failure to invest in capital and, to a lesser extent, in skills. Other countries did not cut back their investments as fast and as far as Britain.

The greater fall of UK productivity growth than other countries is mainly due to lower growth in capital and skills

Note: Comparison of market-economy real value added per hour growth 2019-2007 vs. 2007-1995. Bars represent the contribution of different components (Capital, Skill and TFP) to the slowdown in labour productivity growth. The contribution of capital to the 2 percentage point slowdown in UK productivity growth was greater than in all other countries. TFP = residual Total Factor Productivity. Data from EUKLEMS & INTANProd (2023 release) as well as OECD and other sources.

The authors’ analysis also shows that the United States produces 28% more value added per hour than in the UK – and the French and Germans are 13% and 14% respectively more productive than their British counterparts. And this is in 2019, before the Covid and Ukraine crises.

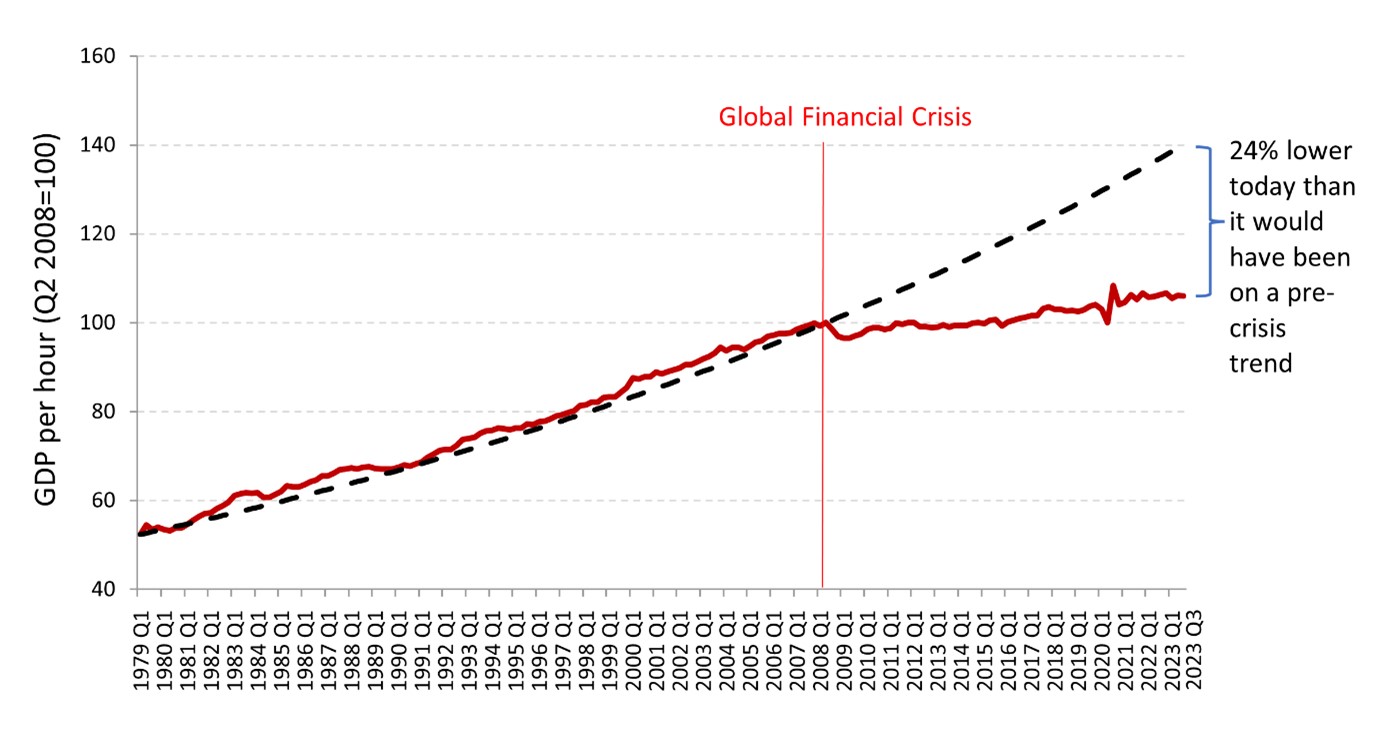

And further analysis of figures released this month by the Office for National Statistics shows productivity in the third quarter of this year is now 24% lower than it would have been had the long-run trend in productivity growth seen before the global financial crisis of 2008 continued. This means Britain has now suffered 15 years of anaemic productivity growth, which has been the major cause of the stagnation in real wages over the same period.

UK Productivity is about a quarter lower than it would have been if it followed a pre-crisis trajectory

Notes: ONS Output per hour worked, UK Whole Economy (2008Q2= 100); Van Reenen and Yang (2023) based on “Productivity flash estimate” 21/11/2023: July to September 2023 and 24/10/23, UK. Predicted value after Q2 2008 is the dashed line calculated assuming a historical average growth rate of 2.2% (the 1979Q1-2008Q2 growth rate).

Reforms seeking to boost business investment were centre stage in last week’s Autumn Statement, including the permanent full expensing of capital investment, and commitment to tackle planning delays.

“I expect the business reforms to increase capital stocks and growth potential over time,” John Van Reenen, report co-author and director of POID, said. “But, from a growth perspective, cuts to public capital investment in future years are particularly concerning.

“The UK productivity problem can be summed up in three words: investment, investment and investment. Or lack thereof.”

The report will be launched at an event today (Monday 27 November)at LSE, when the authors will discuss why UK productivity has been so poor and what policies could restore the country to sustainable growth in the light of the Chancellor’s autumn statement.

Full report available here: Cracking the productivity code: an international comparison of UK productivity by John Van Reenen and Xuyi Yang.