To celebrate Women’s History Month, LSE125 is sharing the stories of five incredible women who have either studied or worked – or both – within our institution.

From leading by example to overt political activism, the legacies of these distinguished women serve to inspire us all today.

Eslanda Robeson

Eslanda Robeson. Credit: UCLA Library Special Collections

Eslanda Robeson. Credit: UCLA Library Special Collections

Eslanda Cordozo Goode Robeson (1895-1965), also known as Essie, was an anti-racist, anti-colonialist, anti-capitalist, and feminist.

She studied at LSE from 1933 to 1935 and again from 1937 to 1938. At LSE, she studied under Bronislaw Malinowski, the Chair of Anthropology, who was considered one of the most important anthropologists of the 20th century.

One of her seminal works was the text African Journey. In this text, she published an anthropological piece that differed from many publications around Africa by calling for an African independence and not pathologising Africa. She opposed the notion of African primitivism and refused to substantiate these types of racist claims, which were rampant in early 20th century anthropological research.

Her political point of view was black autonomy and there was also a globalised emphasis on liberation. She saw the interconnectedness of oppressed peoples and often drew upon the image of a common humanity. Her pan-Africanism led to involvement in the Council of African Affairs, along with W E B Dubois and Paul Robeson, where they pushed for autonomy in Africa. In 1951, she interrupted the United Nations post war conference on genocide to highlight the lynchings and attacks on African Americans between 1945 and 1951.

Eslanda was a unique black woman of her time, who engaged in transnational politics and saw the importance of a globalised perspective. At a time when most African American women were domestics, her story offers a unique point of view on the unravelling of Jim Crow, the Harlem Renaissance, World War II, the Cold War, and the rise of fascism.

Sally Sainsbury

Sally Sainsbury (1939-2013) had worked at LSE for half a century. She first arrived in 1962 to study for the Graduate Diploma in Social Administration, before joining the Department of Social Administration to become a research assistant and a teacher.

Sally worked for five years as research assistant, first with Peter Townsend and then with Brian Abel-Smith. She worked “with” them rather than “for” them because, although she never sought celebrity, she contributed as much to their work as she learned from them. Then, for 35 years Sally was on the teaching staff in the LSE Department of Social Administration.

As a scholar and researcher Sally was a leader in the field of disability and social policy. Perhaps the most important of her many studies was Deaf Worlds. Its importance was widely recognised; one reviewer put it on a par with the great pioneering studies in social policy. It is not easy to evaluate the impact of such a study but it undoubtedly contributed to breaking down the ignorance that existed about deaf people.

She was always considerate and supportive, caring and committed. Through her teaching Sally influenced many hundreds of lives, through her writing many thousands of lives.

Lilian Knowles

Lilian Knowles portrait in Sardinia House. Credit: Jennie Stayner

Lilian Knowles portrait in Sardinia House. Credit: Jennie Stayner

Lillian Knowles (1870-1926) joined LSE in 1895 as a research student and became a permanent lecturer in Economic History in 1904. In 1907 she was promoted to Reader and in 1921 became the first Professor of Economic History at LSE (and the second professor of Economic History in the country). She was the first female Dean of Faculty in the University of London, holding the position of Dean of the Faculty of Economics from 1920 to 1924.

Throughout her life and career she was a pioneer for women, not politically but through her actions, and she advanced her gender by example. In 1904 for instance, she married but she did not give up work. She advocated appropriate pay and, when addressing a group of women, called for collective responsibility to not take a lower rate of pay than the going rate. This was because that action would undercut the labour market and make it difficult for those who could not subsidise their income through family generosity.

It is therefore highly appropriate that she gives her name to not only a hall of residence, but to two student prizes in the Department of Economic History: those for the best set of marks in the first year and the final year of the Department’s Undergraduate degree programmes.

This pioneering woman’s portrait hangs in the Department of Economic History on the fifth floor of Sardinia House.

Herabai and Mithan Tata

LSE often runs in the family with several generations making their way to Houghton Street. Herabai (1879-unknown) and Mithan Tata (1898-1981) were a fantastic mother and daughter duo, who both received an education at LSE.

In 1919 a young Indian woman, Mithan Ardeshir Tata enrolled to study at LSE. Mithan was born in 1898 into a Parsi family in Mumbai (then known as Bombay), the daughter of Herabai and Ardeshir Tata. Herabai was born in 1879 and had married at the age of 16, giving birth to Mithan a year later.

In 1909 Herabai became a Theosophist and in 1911 while on holiday in Kashmir she met Princess Sophia Duleep Singh. Princess Sophia was active in the British suffrage movement and her influence led to both Herabai and Mithan taking up the cause of women’s votes in India.

During her time at LSE, Mithan was one of two students introduced to George V and Queen Mary at the laying of the foundation stone of the Old Building. On April 13 1920 Mithan Tata was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn, only one year after the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act had allowed women to enter public office. On her return to India in 1924 Mithan practised at the Mumbai High Court and became Professor of Law at the Government Law College in Mumbai – the first woman Professor of Law in India.

A recent discovery among the student files reveals that Herabai also registered as a student at LSE. The file indicates that between 1919 and 1922 Herabai followed the Social Science Course and took classes in economics. These included a course on the British constitution and Principles of Economics. However, Herabai had not sat any exams and on her departure in 1923 she asked for a certificate to prove she had attended the courses. The certificate, signed by LSE Director, William Beveridge, was dated 6 December 1923. It concludes: “She was in every way an admirable student”.

Hilde Himmelweit

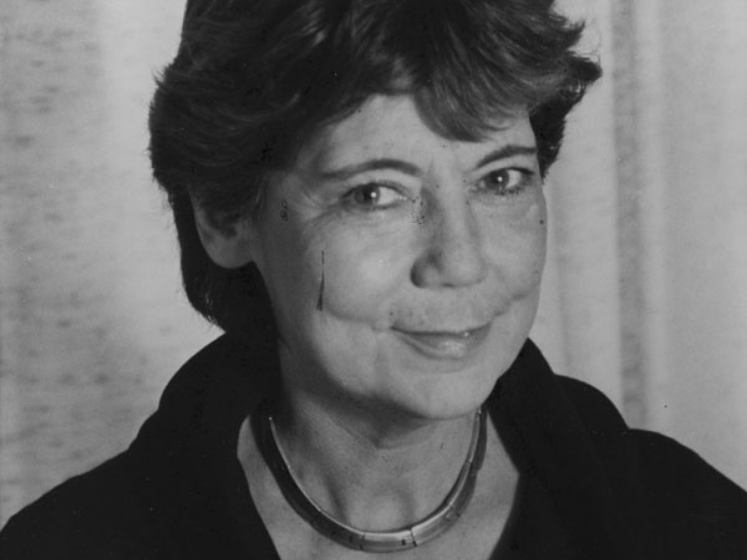

Hilde T Himmelweit, c1983. IMAGELIBRARY/1276. LSE

Hilde T Himmelweit, c1983. IMAGELIBRARY/1276. LSE

In 1946 Hilde Himmelweit (1918-1989) applied for an assistant lectureship in psychology at LSE. In 1949 Hilde was appointed to a permanent lectureship with recognition as a University of London teacher. In the early 1950s Hilde completely overhauled the syllabus for the Diploma in Psychology which was recognised by the Department of Science and Industrial Research for student scholarships. She was promoted to Reader in 1954 moving to the major scale of Readership in 1958.

In 1954 Hilde began a major piece of work which was to shape her career taking on the Directorship of the Nuffield Television Inquiry, an empirical study into the impact of television on children’s lives. Hilde was ambivalent about taking on the role but realised this was a final opportunity to undertake a study with a control group with no regular access to television. Television and the Child was published with A N Oppenheim and P Vince. The report established Hilde’s reputation in Europe and America and led to some heated debates with television personalities.

By the early 1960s the School was deliberating on the future of psychology at LSE including considering the creation of a professorship and a separate Department of Social Psychology. These discussions raised the question of Hilde’s appointment to a professorship and her suitability as a head of department.

When the School decided to advertise the posts externally Hilde, believing the School would not appoint her, decided not to apply. The School Secretary, Harry Kidd, persuaded her to reconsider and after interviews for three candidates Hilde was appointed to the position of professor. She spent the next 20 years developing the Department of Social Psychology (now the Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science).

These profiles have been adapted from LSE History Blog posts by: Professor David Piachaud, Sherese R Taylor, Jennie Stayner and Sue Donnelly. Visit each blog post for further information about the people we have profiled.