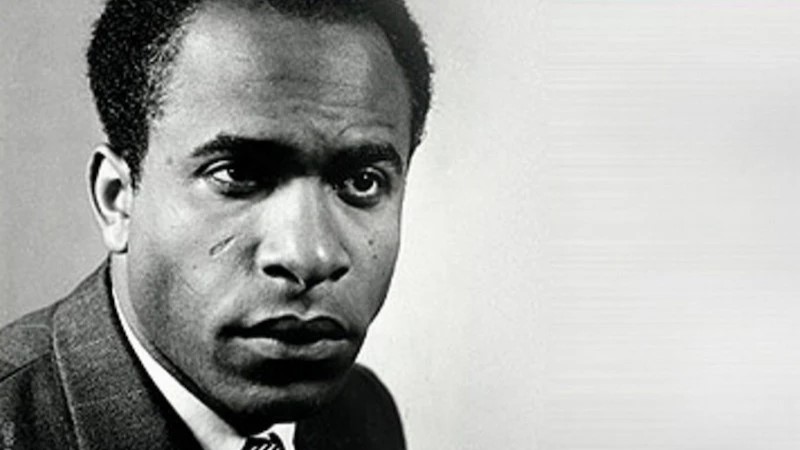

Frantz Fanon was a psychiatrist, diplomat, and scholar whose work has had a major influence on the study of colonialism and de-colonialism.

Frantz Fanon was a psychiatrist, diplomat, and scholar whose work has had a major influence on the study of colonialism and de-colonialism.

Fanon was born a French citizen on the Caribbean island of Martinique. He fought for France in World War II before training as a psychiatrist in Lyon. He moved to Algeria in 1953 where he witnessed the start of the Algerian Revolution against French colonial rule and later joined the Front de Libération Nationale. He was expelled from the country in 1956 and was forced to move to Tunis. There he continued his work for the resistance struggle and as a psychiatrist before serving as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government. He died in Maryland after travelling to the US for leukaemia treatment.

A study of blackness

Fanon published Black Skin, White Masks in 1952 when he was just 27. In it, Fanon examined questions of blackness, racism, and subjectivity. The book looked at how anti-black racism shapes the subjectivity of both the perpetrators and those on the receiving end of such attitudes. Fanon used a mixture of psychoanalysis, philosophy, and lived experiences to make his argument – a method he repeated in his later works.

In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon looked at how language, sexual desire, and recognition shape an individual’s subjectivity.

Language, according to Fanon, is the gateway into a world. To speak a language is to be a participant in a particular civilisation. For many, that can be positive, expanding an individual’s horizons and giving them access to things that would be otherwise unavailable. For the colonised, Fanon argued, speaking the language of your coloniser is to engage in an act of self-colonisation, to embed yourself into a civilisation that is committed to your subjugation, and to engage with and perpetuate the very structures that keep you colonised. To add insult to injury, Fanon said that no matter how fluently a Black man speaks, no matter how fully they embrace the language of the colonising upper classes, they will never be fully accepted by the elite. A black man fluent in French with the crystal cut accent of the leafy Parisian suburbs will more likely be viewed as a curiosity than welcomed in with open arms as if they have passed some kind of test.

No, we do not want to catch up with anyone. What we want is to move forward all the time, night and day, in the company of man, all men

Fanon argued that the white gaze fixes blackness, and in turn, whiteness, reducing the subjectivity of both the gazer and the gazed. In the case of anti-black racism, it creates negative perceptions in the viewer based on alleged weakness and incapacity. For those on the receiving end, it can be internalised, creating an inferiority complex with damaging psychological consequences.

This last point shows how Fanon’s background as a psychiatrist and not a sociologist or political scientist played into his work. In another chapter in the same book, he looked at interracial desire and how the lust for the ‘other’ can be as much about what that body gives you access to in a social capacity as it is about being drawn to the individual or lust for their beauty.

Fanon’s book did not just seek to diagnose problems, as he also looked for solutions. He rejected notions of recognition and validation based on colonial measures of success and acceptance. He went further and asked what blackness could look like after independence, without the institutional white gaze that colonialism has enforced. Fanon does not have a final answer, but he does provide a method: “O my body, always make me a man who questions.” Subjectivity and enquiry are the solutions to the traps of history.

Diagnosing colonialism

Fanon’s move to Algeria led him away from his intellectual investigations into blackness to focus on colonialism more explicitly. His second great work, which dates from this period, is The Wretched of the Earth. The central concern of the book is violence and how it is used on, and by, the colonised.

In Fanon’s reading of colonialism, violence is inevitable because of the perceptions of inferiority the coloniser has about the colonised. The application of violence is a cause and subsequent self-justification for the superiority of the coloniser in their eyes. Initial colonial victories create more economic and military strength and help create the perception of racial inferiority, which in turn justifies the expansion of colonialism and the use of violence.

In response, violence is a show of strength by the colonised that threatens the structures of the colonial system. The shock makes the coloniser aware of the humanity of those demonstrably willing to risk their lives for the hope of a better future.

For Fanon, revolutionary violence is not just about the physical act of defeating a colonial power and removing them from your land. Violence is about freeing the mind as much as it is about material victories. Fanon believed revolutionary violence helps create a collective identity and culture for a new nation and allows it to break with past grieves and instead focus on its subsequent victory as a positive rallying point post-independence.

As with his earlier work, Fanon was interested in what life would be like in a post-colonial world. In The Wretched of the Earth, he examined what humanism would look like if it could be freed from the narrow European conception. What would things look like if they were made for Africa, not for Africa's colonisers? “We must make a new start, develop a new way of thinking, and endeavour to create a new man.”

Resources

A Dying Colonialism (1959)

Black Skin, White Masks, Frantz Fanon.

The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon.

In the New York Times Adam Shatz, the US editor of The London Review of Books and the author of “The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon.” argues that the world has caught up with Fanon.

The documentary film, Concerning Violence uses Fanon's essay by the same name to look at the process of decolonisation.

Standford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy on Fanon.