Introduction

The interwar years saw a surge in publications targeted principally at women who undertook their own housework. An unpredicted increase in suburban house building, cheap mortgages, real wages for blue-collar workers, and a reduction in those willing to enter domestic service, resulted in a sizeable new audience of aspirational working-, lower-middle, and middle-class women craving reliable information, advice, and support. Monthlies such as Good Housekeeping (1922), Woman and Home (1926), and new domestic weeklies such as Woman’s Own (1932), aimed to render what Cynthia White terms ‘intimate personal service’ to these readers.

Involving expert guidance on the best methods and products for feeding, cleaning, and styling a household, these magazines also imagined new identities for women as wives, mothers, daughters, consumers, housewives, homemakers and, particularly at times of economic crises, career professionals with jobs outside the home. Tensions between women’s unpaid work in the home and the more exciting opportunities envisaged in film and fiction, fuelled modern feminine imaginaries. Magazines, with their career columns, adverts for cigarettes and lipsticks targeted at bachelor and business girls, and features debating the fifty-fifty marriage, provided a space for women to imagine, visualise, and address a range of new ambitions and identities, often for the first time.

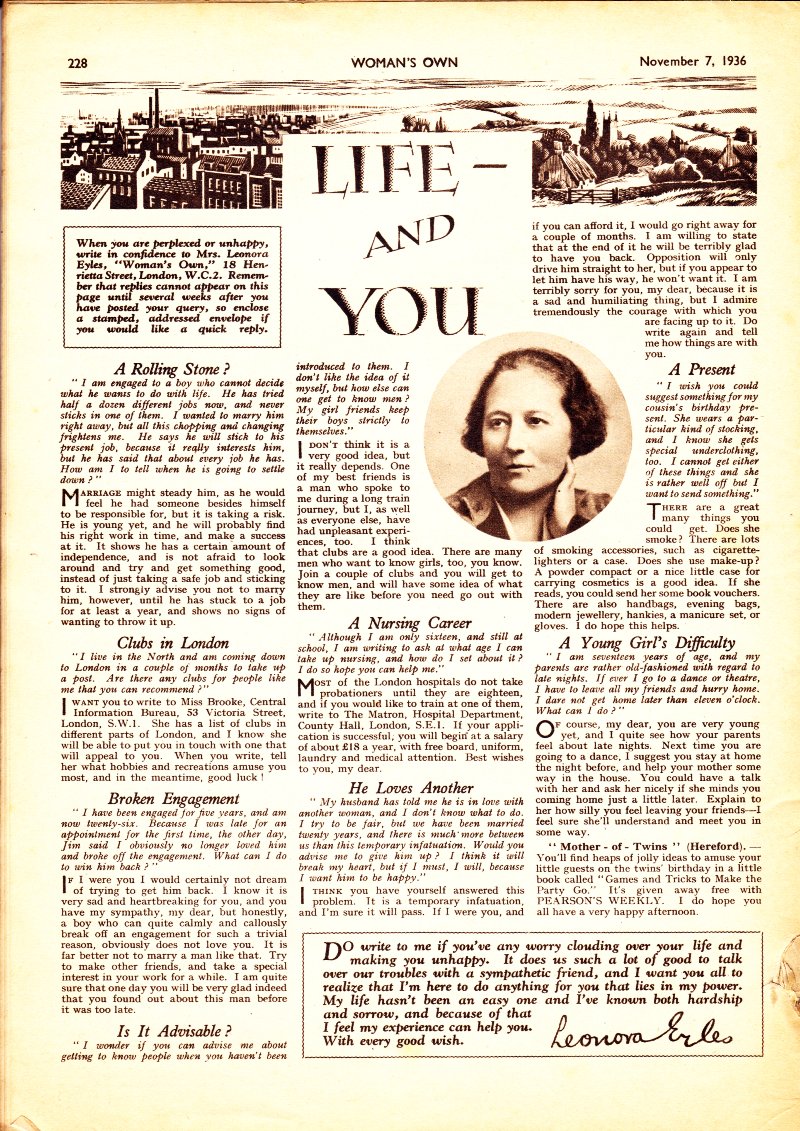

Woman’s Own, 7 November 1936

Margaret Leonora Eyles was a novelist, journalist, and author of such polemical texts as The Woman in the Little House (1922), which was serialised in Time and Tide. A lifelong socialist, her agony columns in the women’s press were as much concerned with sex, motherhood, and employment as with romantic dilemmas.

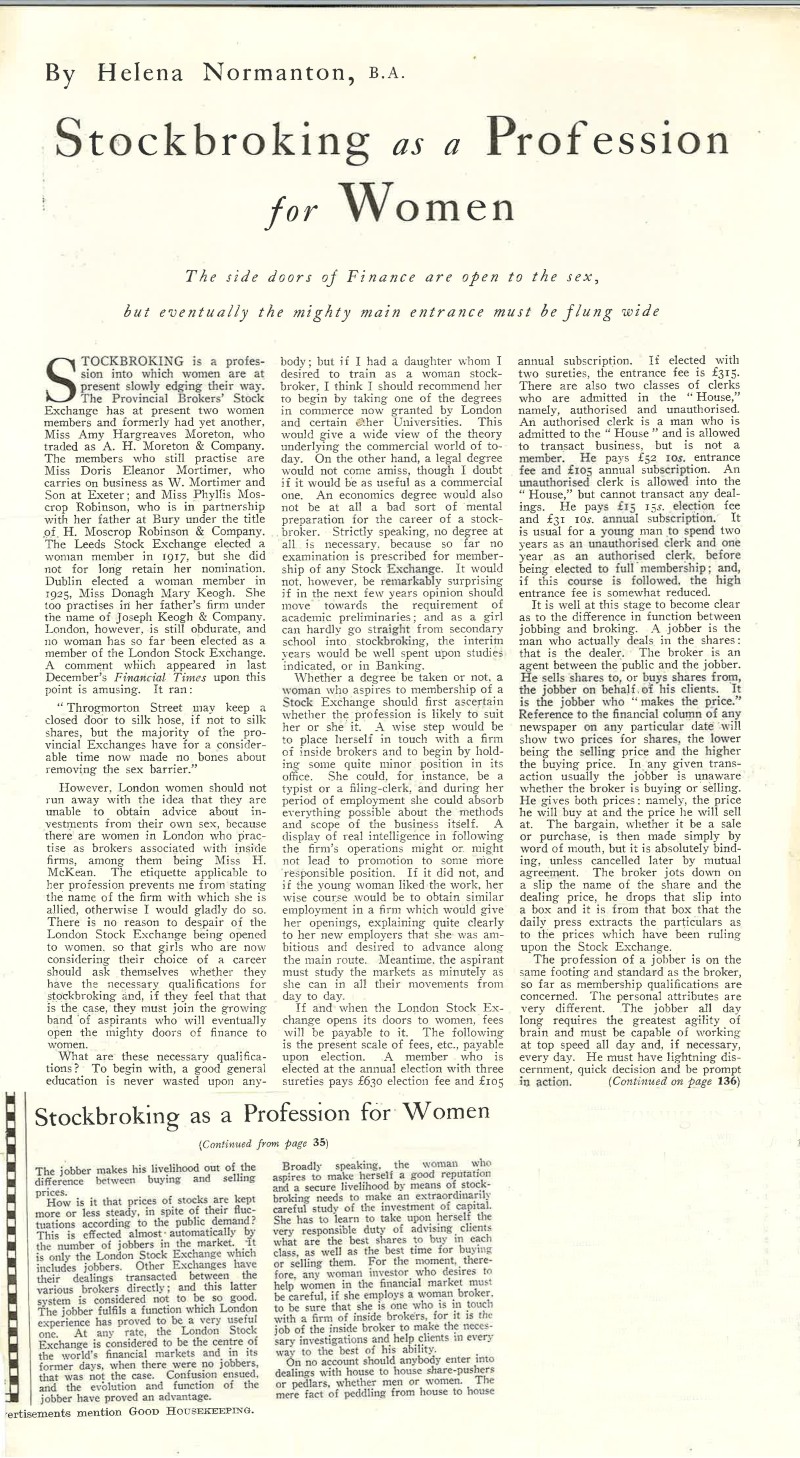

Good Housekeeping, May 1928

In the 1920s Good Housekeeping was concerned with women’s careers as well as their domestic responsibilities. Helena Normanton QC (1882-1957), a pioneering feminist and the first female student at the Bar in England, frequently wrote articles promoting business and the professions as an appropriate realm for women.

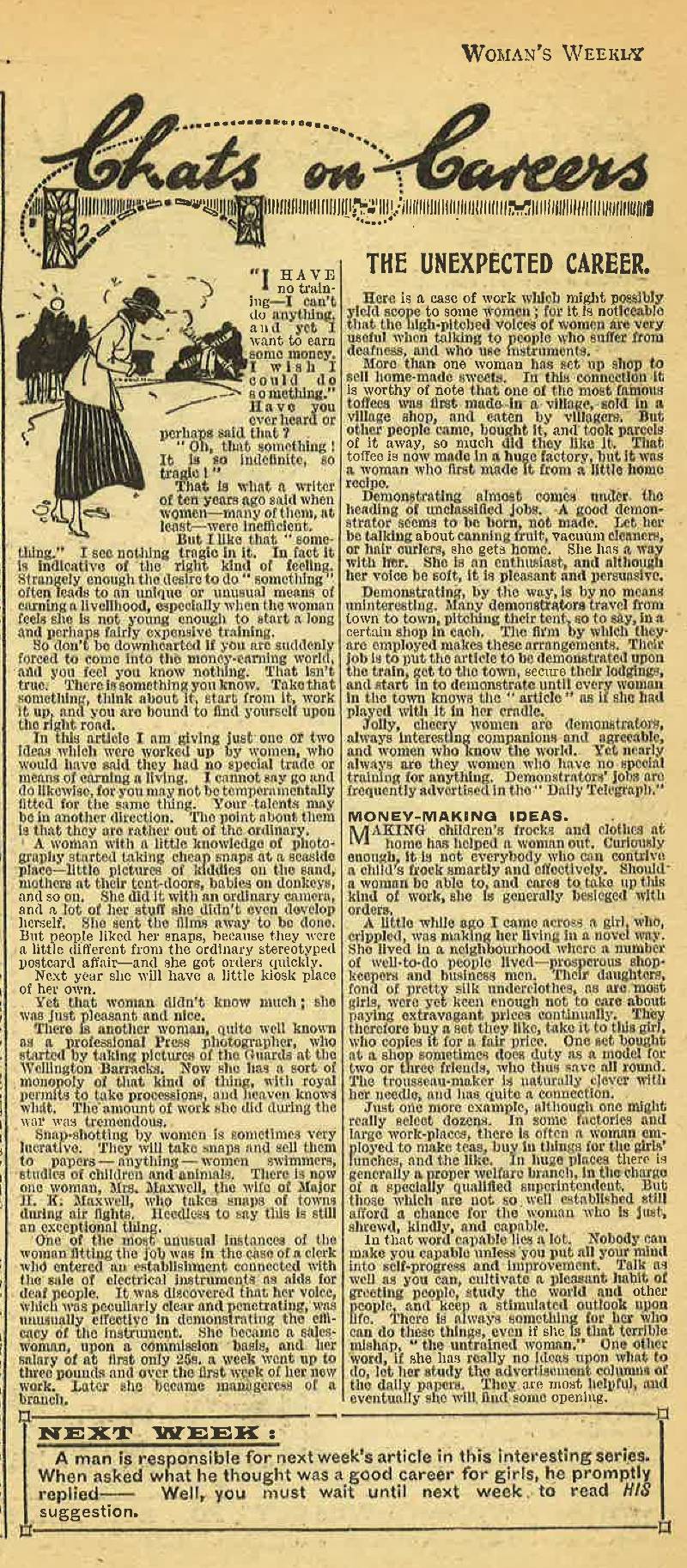

Woman’s Weekly, 18 October 1919

Throughout 1919 this widely read paper aimed at respectable lower-middle and working-class readers ran a weekly career column, signalling the post-war employment crisis for women. Jobs ranged from horticulture to hairdressing but of most concern was ‘that terrible mishap, the “untrained woman”’ who was struggling to survive without benefit of experience or qualifications.

Modern Home, March 1930

Modern Home was one of the new consumer monthlies offering a service to housewives in the interwar years. Home-crafts such as embroidery represented the creative side of home-making, and transfers and dress-patterns were a lucrative source of income for publishers. Floral imagery was central to the new suburban imaginaries forming in the period.

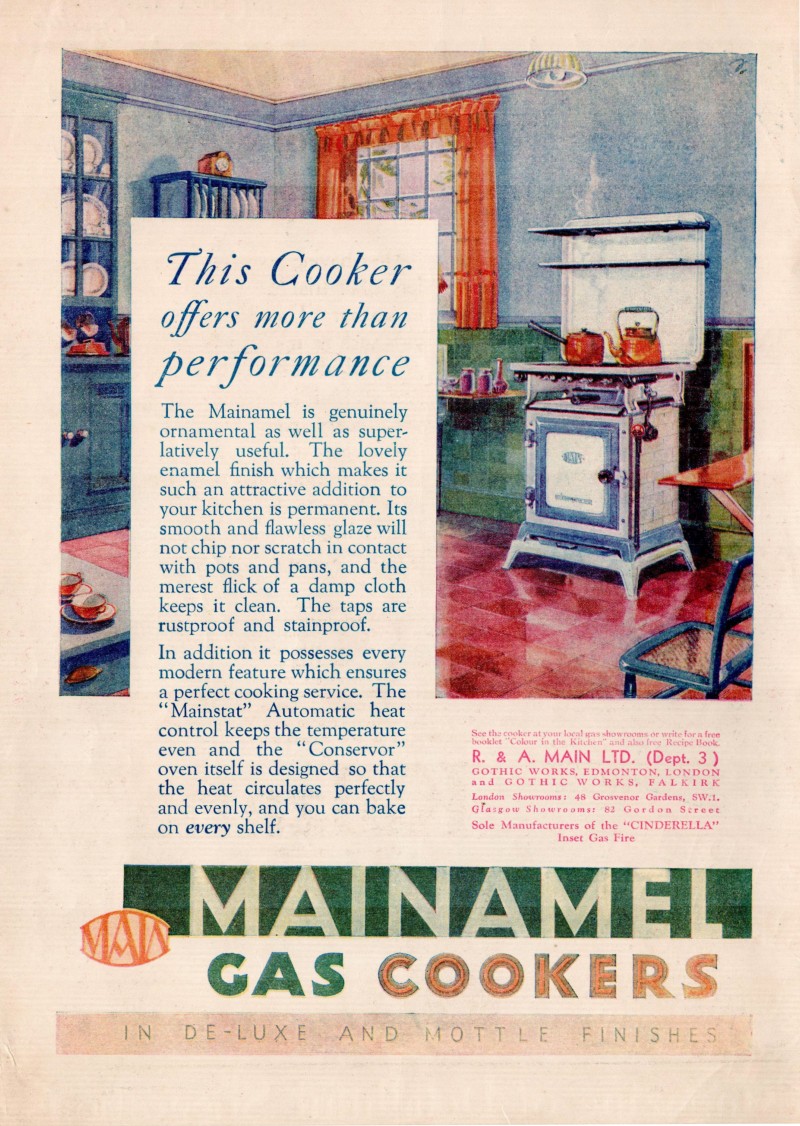

Woman and Home, March 1932*

Modern housework, according to the credo of scientific management, was a science and an art. New domestic ‘labour saving’ appliances promised to modernise housekeeping freeing time for other activities. Monthlies depended on income from advertising and this easy-to-clean gas cooker, rented or on hire purchase, would have been available to the majority of readers.

*Image courtesy Dr Eleanor Reed

Home Chat, 18 May 1929

The cult of motherhood was evident in all domestic magazines. The ideal families depicted, however, had one or two children suggesting the promotion of family limitation through contraception by Marie Stopes and others. A real change in the period, smaller families are also attributed to parents’ aspirations for improved health and opportunities for their children.

Go to the next section