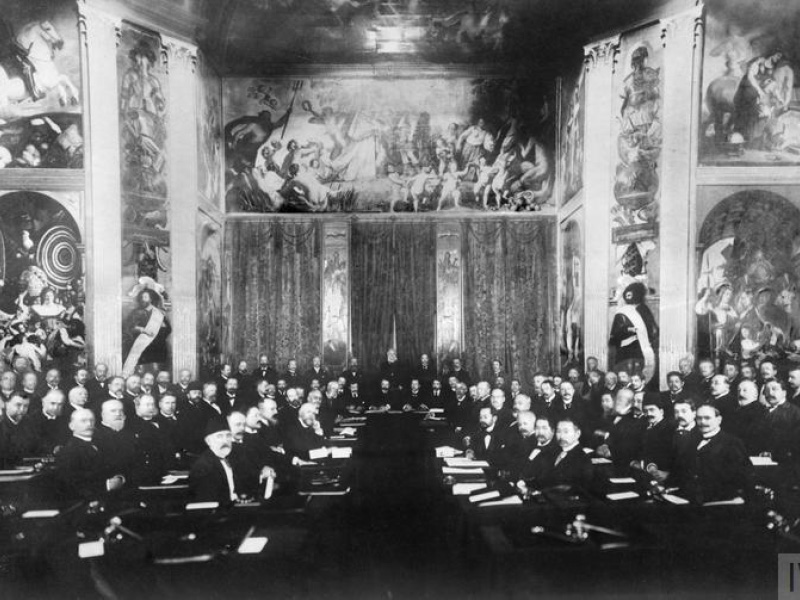

The 1899 Hague Peace Conference was the first international gathering on disarmament. Women were absent from the conference as they lacked political standing in law. No agreement was reached on disarmament.

Feminist peace activists have campaigned actively for universal disarmament since the late nineteenth century. Legal exclusion from the public sphere and political marginalization within mainstream peace movements led many to form women’s organizations committed to universal disarmament and to organise transnationally as they did so in 1915.

In 1915 feminist activists gathered in the Hague to establish the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and adopted a resolution calling for universal disarmament. (Women's International League for Peace and Freedom Records, Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore College).

Click here for Swarthmore College archives.

The adoption of the 1919 Versailles Treaty did little to advance the legal standing of women and inclusion in the political sphere was limited to issues scripted as of concern to women. That said, the very creation of a multilateral institution – the League of Nations – charged with furthering disarmament presented new opportunities for feminist activism.

In particular, the League’s announcement in 1925 of its intention to convene a World Disarmament Conference galvanized peace activists to mobilize nationally and transnationally. For example, in Britain and Ireland, women representing 28 different organizations, including WILPF, organised a Peacemakers’ Pilgrimage to garner nationwide support for disarmament.

The women from Wales were very active in the peace movements of the day and took a leading part in the 1926 peace pilgrimage calling for universal disarmament. See Welsh Centre for International Affairs for an in-depth history. Images courtesy of Bangor University, Archives and Special Collections (BMSS/37223).

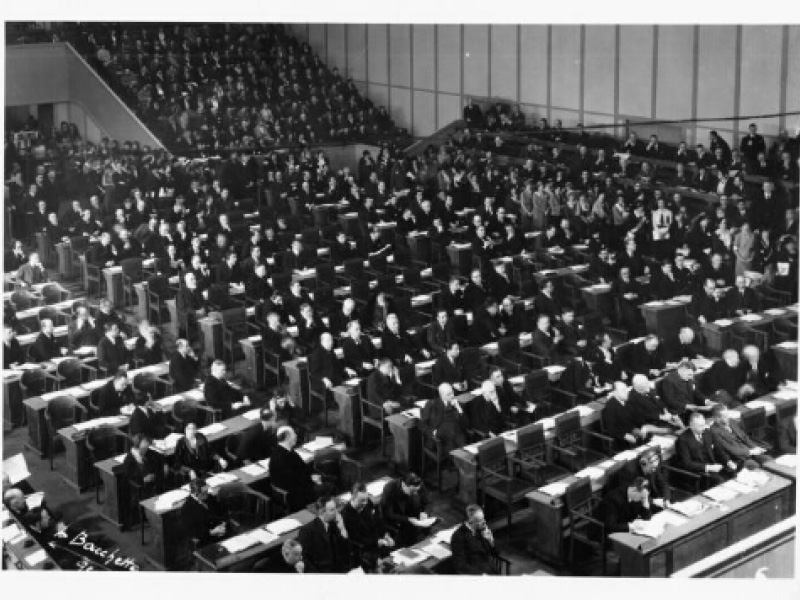

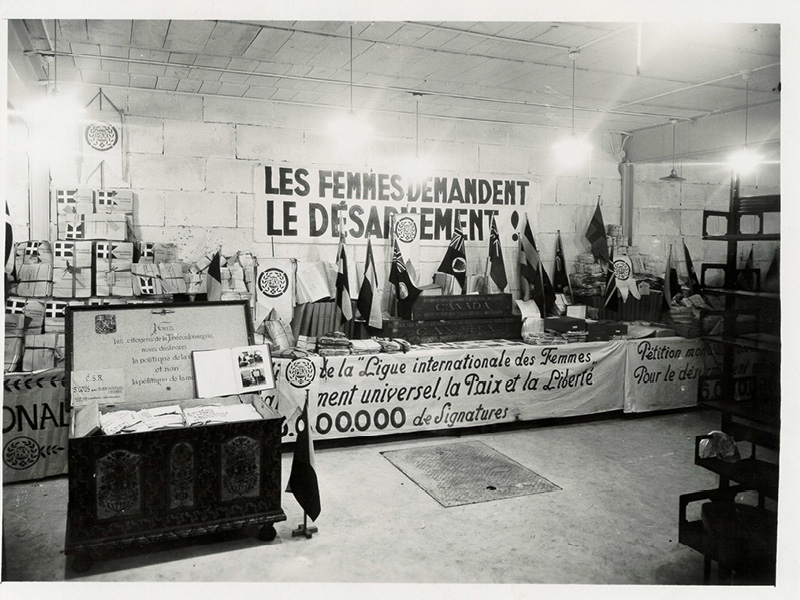

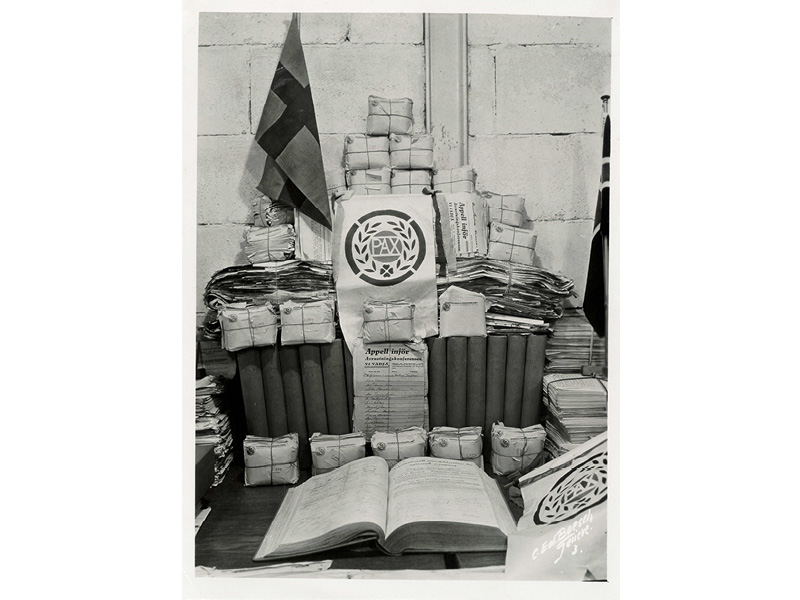

In May 1930, WILPF launced a global petition calling for world disarmament. By the opening of the Conference in February 1932, 8 million signatures had been gathered from different countries across the world which were presented to the delegates in Geneva.

Disarmament, it was reasoned, reduced the likelihood of armed conflict. [Manchester Peoples archives].

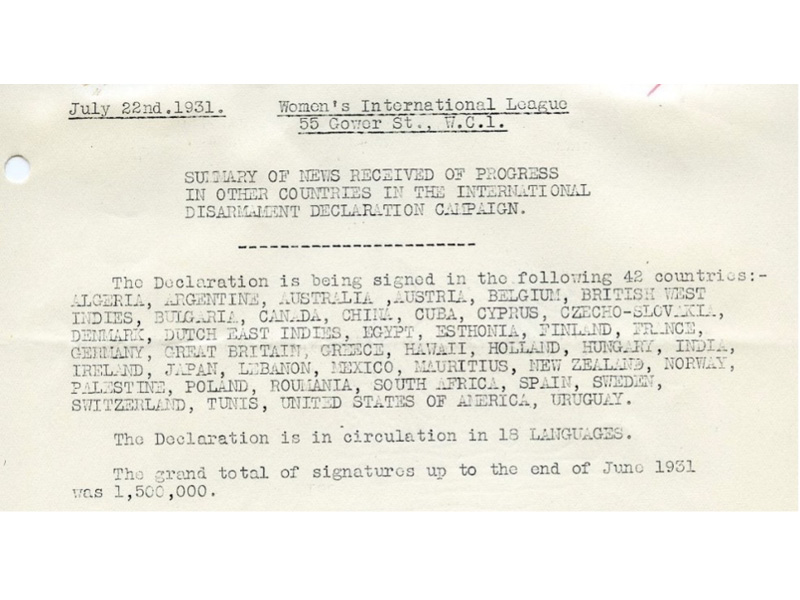

WILPF minutes from July 1931 detailing progress on securing support for the Declaration through its sections across the world [Manchester Peoples archives].

Activists leaving for Geneva with crates packed with the petition Women’s library.

The women queue to present the petition looked on by the delegates [UN archives].

The original petition was likely destroyed during WWII [UN Geneva Archives].

For images from the Women’s Archive, LSE Library, click here.

By the mid-1930s, the Disarmament Conference had all but collapsed amidst rising militarism and a global arms race among states. Transnational feminist peace activism was suspended with the outbreak of World War II

The United Nations headquarters in Geneva is the base for the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Right and the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, the two international institutions that are the site of feminist peace activism.

In the immediate post-war period, women were able to secure an institutional foothold in the newly created UN system and ensure that women’s rights were protected through international instruments guaranteeing non-discrimination, including the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Yet, notwithstanding normative gains, throughout the Cold War period the field of disarmament and arms control was dominated by men.

The escalating arms race among nuclear weapon states together with nuclear testing programmes galvanized a new generation of women to take direct action at the domestic level. For example, in the US, women organised nationally to halt testing while, in the UK, feminist activists mobilized to challenge the deployment of US cruise missiles, most notably at Greenham Common.

Feminist activists have often been at the forefront of challenging the development and the use of weapons by states through non-violent collective action. Some of this work has delivered change. Universal disarmament remains the ultimate objective.

The US-based Women Strike for Peace garnered considerable popular support among mainstream America, leading to one the largest women’s protests of the 20th Century when, on 1 November 1961, 50,000 women marched in 60 cities in the US to demonstrate against nuclear weapons testing [Photo: Harvey Richards Media Archive, Estuary Press).

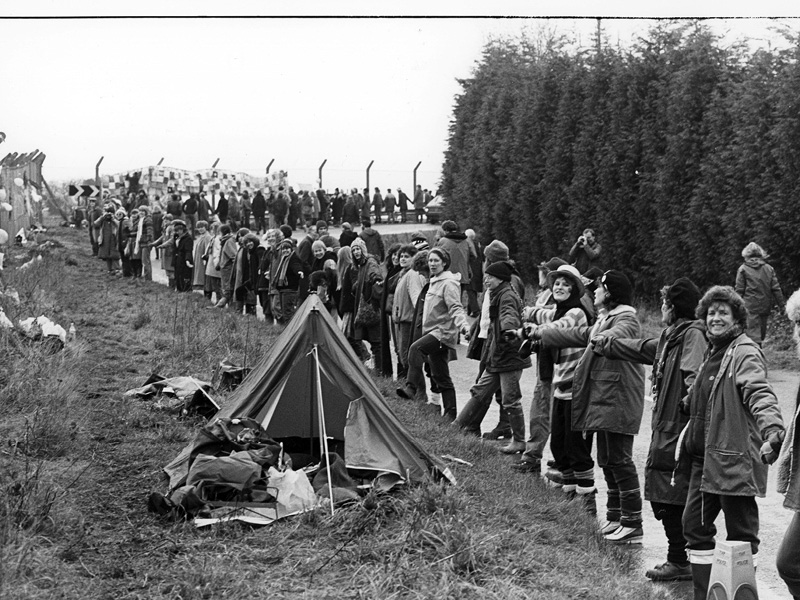

Between 1981 and 2000 feminist peace activists established peace camps at Greenham Common to protest the deployment of US cruise missiles at the RAF base. The missiles were eventually removed, the base closed and the space is now a peace garden dedicated to the disarmament movement (photo: Alamy).

Between 1946 and 1996, the US, UK and France conducted over 300 nuclear test explosions in the Pacific region with devastating humanitarian and environmental consequences. Since gaining self-governance from New Zealand in 1965 much has been achieved by the Cook Islanders through diplomacy, international law, collective action and peaceful protest. Today, the Pacific is a nuclear free zone and testing has stopped. Campaigners continue to press states to provide reparations for the harm caused (photo: Steve Morgan).

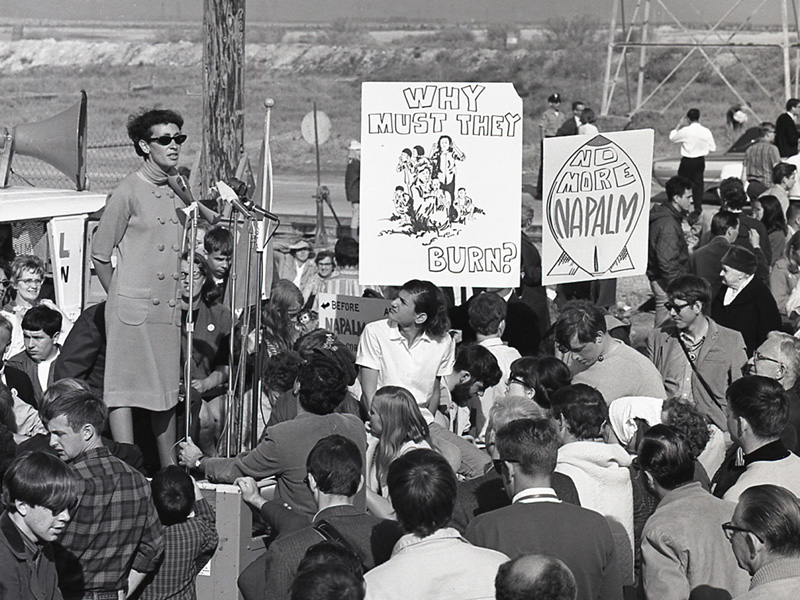

Between 1963 and 1973, over 350,00 tons of napalm was dropped on Vietnam. The effects of the weapon, particularly on the civilian population, produced huge outcry. Feminist peace activists resorted to different strategies from public protest, to lobbying and civil disobedience to stop the use of napalm and to end the war in Indochina. May 1966 Redwood City (Harvey Richards Media Archive, Estuary Press).

Click here to see ‘Napalm Ladies’ – the story of feminist peace activism.